- Karen Conti was a young lawyer when she first met serial killer John Wayne Gacy.

- Gacy was on death row after a jury found him guilty of a horrifying 33 counts of murder after he preyed on young men.

- Fourteen years after his conviction, Gacy was appealing his death sentence when Karen Conti began to represent him.

- She says Gacy, also know as the Killer Clown, was her most haunting client.

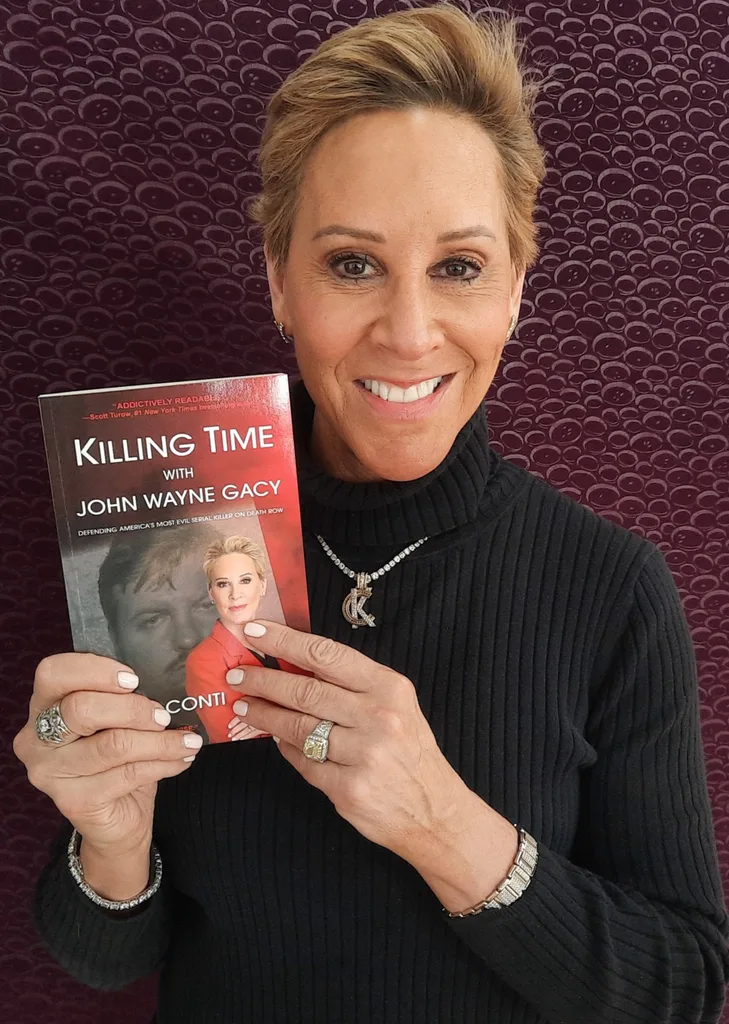

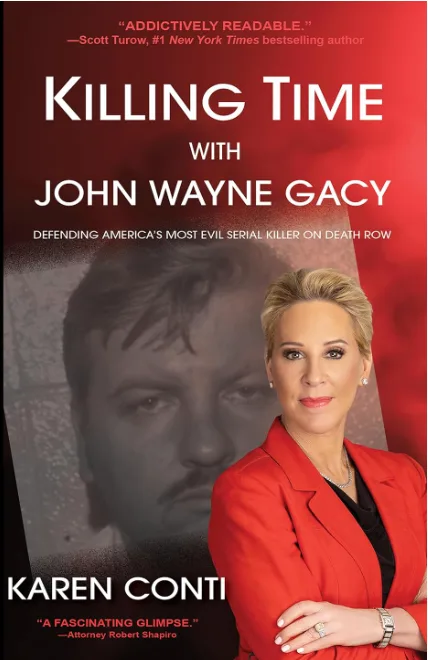

Karen Conti, now 62, shares her story in her own words

I want to look evil in the eye, I thought, walking into a room full of murderers with my partner, and colleague, Greg.

In Menard Correctional Centre, Illinois, US, we were meeting one of the world’s most prolific serial killers – John Wayne Gacy.

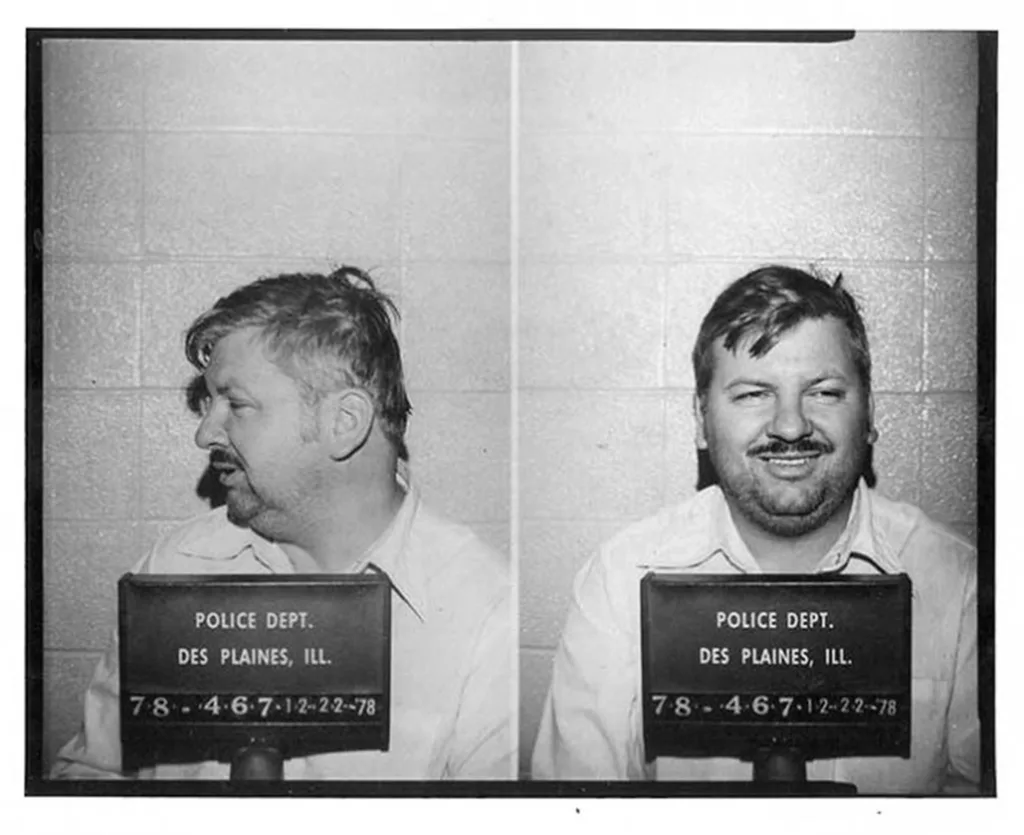

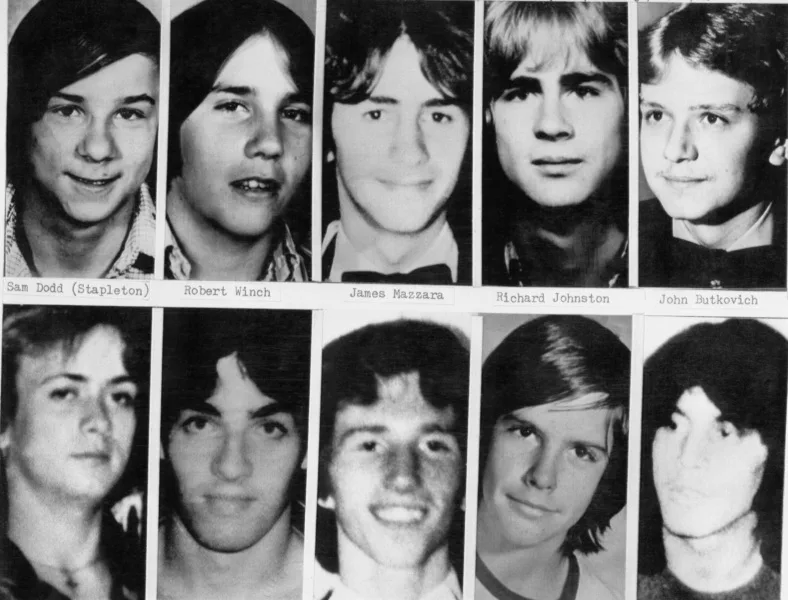

Convicted in March 1980 of the murder of 33 young men and boys, Gacy had been on death row for 13 years. Most of his victims had been buried in the crawl space under his home.

Gacy looked like your slightly dumpy, middle-aged uncle. When he smiled, he was chillingly charming.

‘Hello,’ he said warmly.

Incredibly chatty, he talked about how bad the food was in prison.

As I was growing up, John Wayne Gacy, known as the Killer Clown,was the bogeyman parents used to scare their kids.

The sheer scale of his heinous crimes was horrific. I felt desperately sorry for the victims. But as a young lawyer I was ardently opposed to the death penalty.

I couldn’t support the premeditated killing of a locked up prisoner by a civilised government.

Now, in October 1993, Greg and I had been called to represent Gacy in a row with the prison over selling the artwork he was painting in jail.

Convinced Gacy’s case could shine a light on the need to abolish the death penalty, we offered to join his legal team representing him in death row appeals.

‘Dollface, I already have lawyers,’ Gacy told me.

Like many psychopaths, Gacy needed to have his ego flattered, and I knew we had to give him what he lacked in prison – control.

‘You could use a few more good lawyers. It couldn’t hurt,’ I told him. ‘You’re in control here.’

I said I’d explain to the world why he shouldn’t be executed. ‘Will we sell T-shirts? Free Gacy?’ he joked, agreeing.

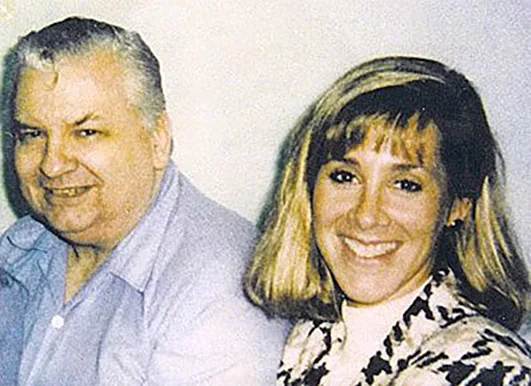

As Greg and I made fortnightly trips over the coming months to speak to Gacy, it became apparent he loved women. If we ever needed to persuade Gacy to do something, he’d often do it for me but not the male lawyers.

Gacy loved his mother and his two sisters, but his father had been abusive and constantly insulted him.

Married twice, Gacy had four children who he loved. He’d been respected in the community and was a churchgoer, who liked to dress as a clown at parades or hospitals.

Hence why he became known as the Killer Clown.

His second wife said he became disinterested in sex, but recalled a strange smell emanating from the space underneath their bedroom.

Could it have been there were already bodies buried there?

One day, Gacy showed me a grotesque notebook labelled The Body Book.

Horrifically, he’d paid a private detective to get photos and news reports of every murder he’d been accused of. He claimed he wanted to make sure the boys who’d been found buried under his house weren’t forgotten, still proclaiming his innocence.

In reality it was a morbid trophy of his horrific kills. Gacy was a true predator.

Plying young men with drink or drugs, he duped them into wearing handcuffs to demonstrate a magic trick then tortured, raped and killed them.

On December 11, 1978, 15-year-old Robert Piest was working at a pharmacy when he met Gacy, who asked him if he wanted a summer job in his construction company.

Tragically, Robert disappeared and, when his mother sent police to Gacy’s house, they were struck by the smell.

Investigating the crawl space under the house, police discovered 27 bodies.

Gacy had buried more in trenches in his driveway and disposed of four bodies in the nearby river.

Police also found school IDs – sickening souvenirs.

I feel sure there were even more victims.

On my 30th birthday, Gacy gave me some gruesome paintings of clowns and a seascape he’d painted in jail.

‘I think of the world as dark and mysterious… like me,’ he told me.

Some experts suggested that in killing the young men, it was like he was killing himself over and over – or that part of himself he was ashamed of, his repressed homosexual tendencies.

‘I’ve been judge, jury and executioner of many people,’ Gacy told his lawyer, despite proclaiming his innocence.

His lawyer had entered an insanity plea, which grated on Gacy. And to me he seemed sane – and without a shred of remorse.

Representing Gacy began to affect my life. Death threats were sent to the office. At my house I found litres of tomato sauce over my front stairs representing the blood of the victims. Friends and even judges warned me not to represent Gacy.

But on May 9, 1994, Gacy’s time was up. As we said goodbye that night he laughed, ‘Your career’s going to skyrocket… You’re gonna be forever connected with me.’

We hugged, then he said, ‘You take care of yourself, Dollface.’

I didn’t watch when Gacy was killed by lethal injection on May 10, at 12.58am. It was a night of conflicting emotions – I didn’t like him, but he was a human being despite his evil actions.

I was glad to get back to other cases, but there was an undeniable hole left by Gacy. He was right, my connection with him and the fight against the death penalty did have an impact on my career.

I lectured in law, became a TV and radio personality, and I remain passionately opposed to the death penalty.

Working with Gacy was fascinating and, despite the atrocities he committed, I hope some good has come from my time with him.

‘Killing time with John Wayne Gacy’, by Karen Conti, is available from Amazon and other book sellers now.

Are Media

Are Media